Conspiracy theorists are spreading disinformation about the torching of RCMP vehicles

In the aftermath of the RCMP raid on the anti-fracking blockade in Mi’kmaq territory, there emerged a conspiracy theory that the six police vehicles set on fire were the act of police informants acting as agent provocateurs.

In particular, one individual has been identified and publicly labelled a police informant: Harrison Friesen. It has been implied that he, along with one or two others, were responsible for several Molotov cocktails thrown at police lines and the torching of the police vehicles in Rexton, New Brunswick.

We saw similar conspiracy theories promoted following the Toronto G20 protests during which four cop cars were burned in the downtown core. Conspiracy theorists said the burnt cruisers were “junk vehicles” planted to incite violence or distract anarchists from reaching the security fence, and that the police set their own cars on fire to justify their massive police operation and violent repression of protesters. Not a single piece of evidence ever emerged to prove these theories about the G20 protests.

More than 40 people were prosecuted for their parts in the June 26th rampage where Toronto Police Headquarters was damaged, shop windows smashed and media vehicles trashed by a breakaway Black Bloc group attacking symbols of capitalism.

But, is it true Harrison Friesen set the RCMP car fires?

His past tells a different story

Friesen, an indigenous rights activist and land defender from Bigstone Cree Nation in northern Alberta came into prominence during the 2010 ‘No Olympics on Stolen Native Land‘ campaign and Toronto G20 as the leader of Red Power United a radical faction from the Red Power Movement.

In May 2010, the media reported, that Red Power activists had announced a day of action on June 24th, just as world leaders would descend on Huntsville, Ont., for the G8 and Toronto for the G20. The group said blockades were planned for either Hwy 400 or Hwy 403. An array of world leaders, including Canada’s PM Stephen Harper, U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Hu Jintao, were to be at the G8 and G20 summits.

Indigenous leadership from reserves had also planned to block major highways on June 24th to protest the Ontario government’s plans to apply Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) towards them. But one week before the blockade, the government decided not to apply the HST to indigenous communities, and band councils cancelled the protest.

But Friesen ignored the wishes of the band councils and announced that he would still be running blockades. This, of course, was something his fellow radicals could agree with because of their dislike for the chief and council system.

It was expected the blockades would interrupt the G8 motorcade, making its way from Huntsville to Toronto for the larger group of Twenty summit. The goal was to draw international media attention to First Nations issues.

Al Jazeera wrote in the article, Canada’s brewing ‘insurgency’, that Friesen’s plans for the blockade “could wreak havoc on the summit and cast light on Canada’s darkest shame.”

Red Power United had intended to show the world that “everything is not okay in Canada for native people”.

CSIS intimidation

Next Friesen agreed to meet with a Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) agent to discuss his plans for a blockade during the G20. He wasn’t meeting as an informant, but instead brought APTN News along to secretly tape. His intention was to embarrass CSIS with the recording.

Activists were provided with a microphone, then from a distance, APTN shot a video showing a CISIS agent talking to Friesen. The female agent warned, that any blockade on Highway 400 would be a “bad idea.” She’s heard saying “I will tell you straight up, there [are] other forces from other countries that will not put up with a blockade in front of their president”. Friesen, told APTN he viewed the agent’s warning as a “threat.”

The woman on the tape also appeared to be seeking information on the anarchist group that claimed responsibility for the May 18 firebombing of a Royal Bank branch in Ottawa. Along with a statement that made reference to Indigenous rights; and the Royal Bank was targeted because it was a sponsor of the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

First Nations groups spoke out publicly about the bombing to establish that it was not done in their name, including the Toronto G20 organizing group for Indigenous Solidarity actions on June 24. Red Power United also spoke out against the arson saying their group denounced such violence.

None of the men linked to the RBC firebombing were Indigenous.

However, the statement condemning the bombing had garnered backlash for Friesen from his radical comrades.

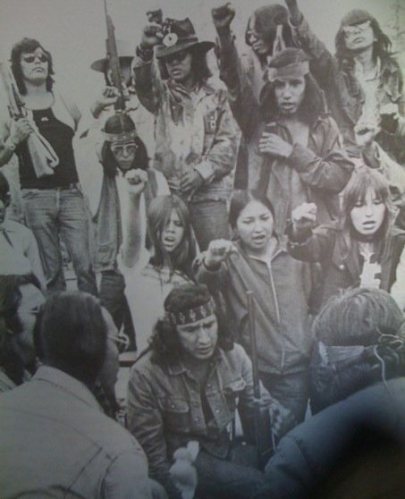

G20, Red Power United, Harrison Friesen (in the Public Enemies T-shirt) engages Toronto police officers. Photo: Isha Thompson Windspeaker

In the end, the G20 blockades never happened. Although it was rumored Friesen’s group had lost support, sources from within the movement told Red Power Media the blockade was called off due to security concerns that another group of protesters were going to attempt to breach the G20 fence on June 24th, possibly endangering peaceful First Nations demonstrators. The blockaders were told to stand down and take on peacekeeping duties.

Intelligence reports

The G20 summit was one of the largest domestic intelligence operations in Canadian history. An RCMP -led joint intelligence group (JIG) collaborated with provincial and local police to do threat assessments, run undercover operations and monitor activists. The surveillance was widespread. And RCMP records suggest that the reconnaissance continued. Report logs indicate at least 29 incidents of police surveillance between the end of the G20 summit and April 2011.

In Oct 2011, The Globe and Mail reported, that a military intelligence unit had assembled at least eight reports on the activities of native organizations between January 2010, and July 2011. The documents alerted the military to events such as native plans for a protest blockade of Highway 401, and the possibility of a backlash among aboriginal groups over Ontario’s introduction of the HST. The memos also devoted a lot of space to future protests and lobbying on Parliament Hill by native groups, including Red Power United.

On October 19, 2013, wrote an article A Fog Of War Surrounding New Brunswick Protest which included a photo that was being shared on social media as proof that Harrison Friesen is guilty for the burning the RCMP vehicles.

“I began asking questions right away, to anyone I saw posting it” said Wilson, asking for further evidence. “I have been told about his apparent history of violence and extreme actions. Been told that people have spoken to people, who say he did it, And much more like that. But nothing that constitutes as evidence. It seems to be a lot of conjecture by people who are not there and are looking for a way to separate violent actions from the protesters and direct it to the RCMP.”

Smear campaigns

Unfortunately, not all media outlets or bloggers can be trusted either, it is well known co-ops across the country, rabble.ca, occupy, etc., have engaged in tactics of slander against many activists and journalists alike to discredit those they disagree with or eliminate any rivals within circles. Labeling First Nations radicals like Friesen, as CSIS agents, CIA or Police ‘informants’, racists, and just about anything they can come up with to demonize people. They will repeatedly throw out false claims. The Halifax media co-op is also responsible for putting out incorrect information about Friesen in Rexton.

Meanwhile some supporters of Friesen believe a possibility exists he was the target of a RCMP smear campaign to break up an alliance between the Mi’kmaq warrior society and the Red Power United faction, whose plan was to help prolong the siege of SWN fracking equipment and fortify the encampment.

State law enforcement agencies such as the RCMP have been known to spread disinformation and even tell flat out lies. In 1995, during the Gustafsen Lake Standoff, RCMP officers were caught on video planning mass media smear campaigns against the Native protesters.

To backup the claim that police would participate in burning their own vehicles again, conspiracy theorists found an actual example of the RCMP blowing up an oil installation. In 2000, a Canadian lawyer exposed in court a RCMP-big business conspiracy, when a unit of the RCMP executed a false-flag bombing on an oil site in Alberta. The oil company in question colluded with the Mounties in the staged attack, then blamed it on anti-oilpatch activist Wiebo Ludwig.

In the article Statement on Provocateurs, Informants, and the conflict in New Brunswick in Warrior Publications, Zig Zag, writes, according to those re-posting this old bit of news, if the RCMP would blow up an “oil installation” in northern Alberta, what’s to stop them from torching their own vehicles in New Brunswick?

In New Brunswick, we are told, it was to justify the acts of repression carried out by the RCMP. But those acts of repression were already in motion, long before the police cars were set on fire. In their own statements, the RCMP justify their raid on the basis of alleged threats made to SWN employees, the presence of firearms, and general concerns for public safety.

If police are going to go through the efforts of staging an attack on their own resources, it is only logical they would do this prior to a raid thereby justifying the raid itself. It is highly unlikely they would instruct an informant to do so after the raid has begun, a raid already justified by “public safety” concerns, etc.

In fact, the burning of the six police vehicles appears to be a response to the raid. But there are those who seek to dampen the fighting spirit of our warriors by implying that any act of militant resistance is a police conspiracy. Some of these people are pacifists, ideologically committed to nonviolent acts, while some are conspiracy theorists who see the hand of the “Illuminati” behind any acts of resistance.

Documents give new insight

Earlier in 2014, a provincial court judge granted an RCMP request to have access to videotape and photographs taken by CBC News and four other media organizations during a clash between police and anti-shale gas protesters in Rexton. A production order was granted by Judge Anne Horsman in Moncton provincial court. The documents filed with the court offer new insight into the events of Oct. 17, 2013, and what led up to it.

The names of confidential RCMP informants, those suspected of setting fire to the RCMP’s vehicles (Page 11), and witnesses are also among the information. The redacted documents include photographs taken by the RCMP’s high-altitude surveillance plane that show “two individuals who appeared to be responsible for the lighting of three of the RCMP vehicles on fire, however the three other RCMP vehicles were already burning.”

This still image from video taken by the RCMP’s high altitude surveillance plane is the best image police have of the two people allegedly responsible for burning a marked RCMP SUV and an RCMP truck on Oct. 17, 2013.

Police also said someone attempted to burn down the local RCMP station in the middle of the night after the raid. Although, 2 Mi’kmaq warriors were charged with throwing the Molotov cocktails at police during the protest that turned violent. No charges were laid in connection with the RCMP vehicles being set on fire.

A Public Statement by Harrison Friesen:

I want it to be known that I did not light any police cars on fire in Rexton NB and that I am neither a provocateur nor informant. If anything I’m a hated and targeted by law enforcement agencies just like many indigenous activists who defend our sovereignty are. What occurred on social media, was a result of conspiracy theorists, which was then fueled by those enemies I made because of past mistakes. I was also personally targeted because of my past involvement with AIM protests and the fact that I am supporter of both the AIM Movement and Leonard Peltier. Although Elsipogtog territory is that of the late Annie Mae Aquash and I did not know this going into that action, it still would not have swayed the decision I made to help the Mi’kmaq people protect their water. I only went to Rexton NB as a direct action trainer and peacekeeper from the Red Power Movement, our presence was requested by the Mi’kmaq people from Elsipogtog to help avoid violence. As for the RCMP cars that were burned that day, my only comment is: “It was a protest and people were pissed off because of police repression, it happens.”

This is what one radical journalist, an eyewitness present during the conflict on Oct 17, stated about the burned cop cars and the theories of who burned them:

“To all the people spreading misinfo about provocateurs at Elsipogtog, listen up. RCMP cars were not burned by provocateurs. It was an expression of rage by an angry crowd sick of being trampled by the government. People put their cameras away as the cars were being lit, as to not incriminate comrades and cheered every time one went up in flames. Hundreds of people witnessed this, so drop all the propaganda and snitch jacketing and raise your glass to all the brave peeps who risked life and limb to protect your fuckin water.” – The Stimulator, Oct 18, 2013.

From Warrior Publications:

“In the past, it was common sense that you did not label a person a police informant without substantial evidence. Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence. Informants and police infiltrators have been exposed in the past based on real evidence, through court transcripts or intercepted communications with their handlers, for example. At this point, Harrison is being made a scapegoat by those pacifists and conspiracy theorists who are either opposed to militant resistance on principle, or who see a government conspiracy behind any spectacular event.”

“So far, we have no evidence that Harrison Friesen is an informant or that any agents provocateurs set the cop cars on fire in New Brunswick. And until such evidence is produced, those circulating unsubstantiated claims should cease doing so.” – Zig Zag, Oct 18, 2013.

It is well known there are ongoing efforts by law enforcement agencies to infiltrate, disorganize and destroy Indigenous resistance movements ― such as the one led by Friesen, which the State considers a threat.

The police have also been known to create fake social media accounts used to obtain information and interfere with activists activities. As it turns out, a Twitter user who goes by the handle @BigPicGuy, Mark McCaw was the original source who attempted to label Friesen as an agent provocateur.

Despite social media speculation about police provocateurs torching their own cars, an eyewitness said the vandalism was carried out by known anti-fracking warriors from Mi’kmaq territory.

There is no proof that Friesen or any member of Red Power United were responsible for the throwing of molotovs or the burning of the RCMP vehicles in Rexton. To date, not a single piece of evidence has surfaced to justify the allegation.

Editor’s Note: This blog post was is a collaborative writing with research done by Red Power Media, Staff and originally published in Oct. 2013. It has been revamped and updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness.